Inspirations

Patricia Van Ness

Mrs. Van Ness was my kindergarten teacher. Only two years ago, I learned exactly how lucky that was. What I remember from then is that she was very strict, that my handwriting has never looked as good as it did when I was five… and that she taught me to read in half an hour. To explain, we were sometime into early spring, and most of the class was picking up the basics of reading. But not me – the basic concepts weren’t sticking, it wasn’t making sense, and nothing she said to the class seemed to penetrate through the wall of incomprehension. It was making me frustrated and upset and I was starting to hate school. And then, one day, I missed the bus.

I wish with all my heart I could remember what she said to me during the thirty minutes while we waited for my mother to come get me. I’ve wished that a hundred thousand times and I wish I had thought to try to find her and ask before she passed from this world. But whatever she said, she taught me to read in the 30 minutes we waited for my mother. I remember a feeling like pieces clicking into place and suddenly I could read anything. Less than a year later I was multiple books into the Ramona the Pest series and continued to devour literature like it was oxygen and I was drowning.

It was from her obituary that I learned that Mrs. Van Ness was a pioneer of neurodivergent education. In 1968, she left Princeton for three years to teach at the Mercer County Child Guidance Center for autistic children. And I’m certain it was that background that allowed her to explain reading to me from an angle that let me understand it in a way I hadn’t before that. This amazing woman gave me literally the entire world. I’ve been a book worm ever since that day, and it has literally saved my life on more than one occasion. It also gifted me with a profession that requires a great deal of reading and research – things I love because I didn’t continue to struggle for years to try to learn this basic skill that is so central to them.

I will always be grateful, the ability to read is beyond invaluable, and a love of reading has been one of the greatest gifts of my life. I watched another struggle to learn to read for years, and while they eventually did learn, they have never truly enjoyed it, never turned to it as a voluntary past time. Too much of their emotions towards it are tied to the frustration of just not getting it for years. And without Mrs. Van Ness, that would have been me – instead of the child causing the dilemma for her parents by still reading long after bedtime. That was this amazing woman’s gift to me – and she gave it to every student she could. Most of us left kindergarten fully literate – and how many kids can say that? And that willingness to spend the little extra time with me taught me what a world of difference just a little time and energy can make in a life.

Her greatest gift to me is I can focus fully on what something says – rather than on having to actually read it because it is so much a part of me now. This allows me to focus fully when I’m researching, going through evidence, checking a plea agreement for hidden traps – because my mind is entirely on what I’m reading, never on the act of reading itself. But the other is that a little time taken now can change lives – and so I always make sure to spend a little time just talking to my clients. Not about their case, just talking – getting to know them and what they are going through. That is often where the strongest defenses come from – but it is also just important to take the time. We all feel it when someone takes the time to actually pay attention, and I try to give that to all of my clients where possible.

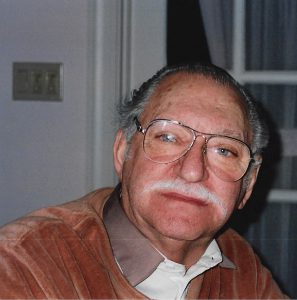

Louis Kremen

My grandfather was born in Latvia, where he suffered from Polio as a child. He was told he would never walk again, but after a year of struggle he was able to. He emigrated to the United States and served in the Air Force in World War II, where his plane was shot down. In the process, he lost all his teeth and spent many years with ill-fitting dentures until, when I was a teenager, he was finally given implants by the VA.

Throughout my life, my grandfather suffered from any number of physical issues from his spine to his teeth, and over time he became less and less mobile – moving to a walker, then a scooter. But he never once complained, he was always there with a willing ear and a warm hug. He lived his life without bitterness, despite everything the world cost him, and he loved without reservation.

When he came to this country, my grandfather was an orthodox Jew. But he met my grandmother, who was a divorcee, and no orthodox rabbi would marry them, as her first husband not only didn’t provide her with the right Jewish paperwork for divorce, but he also wasn’t even Jewish. And so, my grandfather turned his back on orthodoxy, became a reformed Jew, and married her anyway. That is the kind of love he gave to everyone who mattered – he put people first.

I was just barely 18 years old, literally a matter of weeks, when they told me I had an auto-immune disorder and would never be truly healthy again. That some of the discomfort and pain I was dealing with would be with me for the rest of my life. And it tore my world apart. My grandfather never actually spoke with me about that in particular, though I think I’m the only one of his grandchildren to have had a private joke with him (we both promised to let one another know as soon as we found the body part store for replacement parts). He was just his usual quiet, gentle self – listening and present. And suffering from chronic pain, unable to walk any longer for any length of time and fighting all attempts to drug him because he didn’t like how the pain medication made him feel.

By example, and in subtle, quiet ways, my grandfather taught me empathy and kindness. He never said it with words, but it became clear to me from his actions that my options were to be angry with the world for what it couldn’t be – or to be happy. You can’t truly be both because you cannot be angry and happy simultaneously. It’s not that I never rage at the frustrations of my body, as with any other frustration in life, but he taught me not to let it consume me. And that was the first lesson in a series that I learned from this.

The next thing I learned was that pain is relevant, not relative. As in, it does not matter how much more objective pain one person might be in as opposed to someone else, because that means nothing at all. I may be in more objective pain than any healthy 10-year-old has ever experienced day to day, but if that 10-year-old just broke her wrist, her pain is much more immediate and real in this moment than my own, which is shoved to a back corner of my mind. And therefore, in that moment, the girl’s pain is more important than my own. The ability to recognize pain in others as real and needing care – that was the gift of learning to be less angry. To recognize that others around me are also suffering – and that I can help. That last part, that’s what I needed to learn more than anything else.

My grandfather gave me the gift of channeling my own pain into helping other people, in his quiet, gentle way. The ability to recognize and feel others’ pain, to open yourself to it, isn’t always pleasant – any more than living with chronic illness means they are all good days. However, what it does do is make it have meaning. From him, and from what he showed me, I developed a philosophy I call conscious kindness – trying to do what I would wish others would do for me, whenever possible. Because the world can be a terrible place – but it doesn’t have to be. We, humanity, make the world we live in. So, I shall continue to try to build a world I would want to live in, by doing for others what I wish someone would do for me in their situation, as much as I can.

In the two years and change of the pandemic, I have heard hundreds of times “you have to help yourself, no one else will”. But the reality of that has never been true – humans are herd animals, and we need one another. No one truly does it all alone, save perhaps the hermit living in the woods, growing their own food, and using no electricity or internet or running water. But for the rest of us, we depend on other people every single day – to eat, to get where we’re going, to make sure that our children get to school and learn while they are there, and so on. The idea that we can or should do it all ourselves is poisonous – sometimes, you need help. And that’s ok. And sometimes, you’re the one who can give that help – and that’s a gift.

I’ve had multiple opportunities to change to areas of practice that are less centered directly on people in need – but while they might be easier on my heart, they would be lacking something I consider essential. I need to be helping people, as directly as possible. It’s a need that springs from the empathy and understanding my grandfather taught me, as well as everything my parents taught me growing up. And I have a knack for the logic and out-of-the-box thinking necessary for trial work. So, to me, using that skill set to help as many people as possible is a goal worth pursuing for a lifetime. Too often in our society, we look away from that which is uncomfortable – and our justice system isn’t a comfortable thing to look at for very long. But if we look away, if we stop fighting, that’s when injustice wins. The system needs to be fair, and everyone deserves someone on their side, fighting for what they want from life – regardless of what they’ve done or been accused of. And my grandfather’s gifts of empathy and learning to really listen mean that I can be that person.